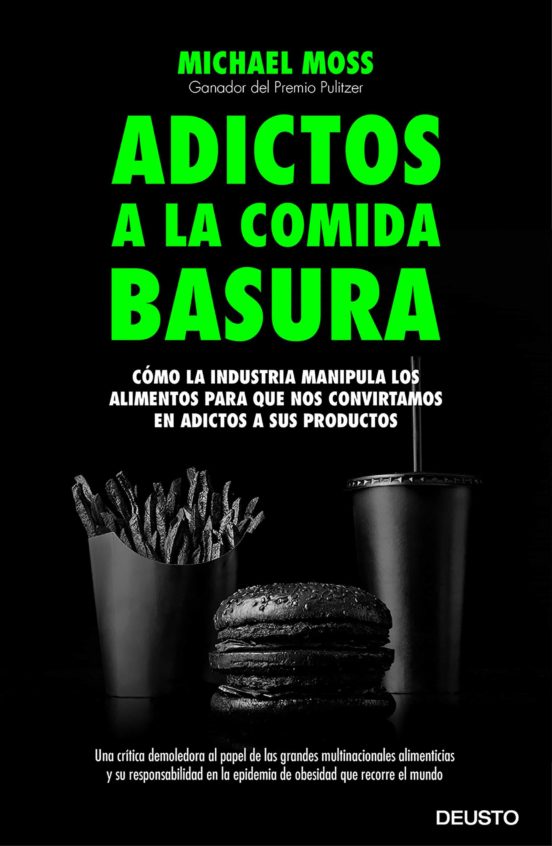

Food campaigners on both sides of the Atlantic have been saying as much for decades. There's nothing earth-shatteringly new in Moss's assertion that sugar, salt and fat are the unholy trinity of bad food. Without salt, he observes, "processed food companies cease to exist".

Sugar, with its "high-speed, blunt assault on our brains", is the "methamphetamine of processed food ingredients", he believes, while fat is the opiate, "a smooth operator whose effects are less obvious, but no less powerful". Their job is to establish the necessary "bliss point", the precise amount of sugar, fat or salt guaranteed to "send consumers over the moon". By deliberately manipulating three key ingredients – salt, sugar and fat – that act much like drugs, racing along the same pathways and neural circuitry to reach the brain's pleasure zones, the food and drink industry has created an elastic formula for a never-ending procession of lucrative products.Īs Moss explains, the exact formulations of addictive junk foods (and drinks) are not accidental but calculated and perfected by scientists "who know very well what they are doing".

How do the food giants do it? Moss's central thesis is that junk food is a legalised type of narcotic. What he uncovered is chilling: a hard-working industry composed of well-paid, smart, personable professionals, all keenly focused on keeping us hooked on ever more ingenious junk foods an industry that thinks of us not as customers, or even consumers, but as potential "heavy users". He interviewed hundreds of current and former food industry insiders – chemists, nutrition scientists, behavioural biologists, food technologists, marketing executives, package designers, chief executives and lobbyists. The feta cheese, spinach pies, and green olives have large amounts of salt.New York Times journalist Michael Moss spent three-and-a-half years working out how big food companies get away with churning out products that undermine the health of those who eat them. A biologist, he studies salt in fruit flies, which have comparable tastes to humans. Common food products contain hundreds of milligrams per cup. For at-risk populations, which comprises more than half the American population, the number is 1,500 milligrams of salt.

The government recommends a maximum daily sodium intake of 2,300 milligrams.

Cargill, the largest salt producer, says that people love salt. Moss writes that the food industry uses salt to increase sales. In previous times, people ate salted products that contained far more sodium than now, using salt as a preservative. Packaged foods carried far more salt than people added from salt shakers. Food scientists at Monell analyzed the sources of dietary salt. Men, especially, consumed large amounts of salt. Some groups pressured Americans to abandon their salt shakers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)